The Density of Information in Communication

Imagine you’re strolling through London on a vacation, absorbing the city’s vibrant sights. As you turn into Baker Street, a man donning a coat and an unusual hat approaches you.

“Greetings, young man. Are you aware of the wealth of information you’re communicating?”

“I’m sorry, I don’t follow. What do you mean?”

“You see, I had a wager with my friend Dr. Watson here. Allow me to make some educated guesses about you. Your smartwatch, complexion, and muscle composition suggest that you likely jog for health reasons.”

“… that is correct.”

“Your curious gaze around indicates that you’re not a local, so you’re either a tourist or visiting a friend. Your accent is distinctly German.”

“Yes”

“Have I satisfied your curiosity, Watson?”

Another man appears, responding to the question.

“I’m not sure, Sherlock. All of that seemed rather obvious. Can’t you deduce anything else?”

Can he, though? What kind of information can you glean from a person? Let’s delve into the things you could theoretically know about a person if you were extraordinarily intelligent.

Sight

When you meet a new person, the first impression is usually visual. You observe their face, attire, gait, and body posture. You notice if they’re wearing a watch, glasses, or jewelry. All these details can offer insights about the person, but there’s much more to it:

- “Gaydars” exist and can be surprisingly accurate. Machines significantly outperform humans 1

- This is stable and probably not just makeup 2 AND better than humans

- Moreover, AI can deduce political orientation better than chance from a single image! 3

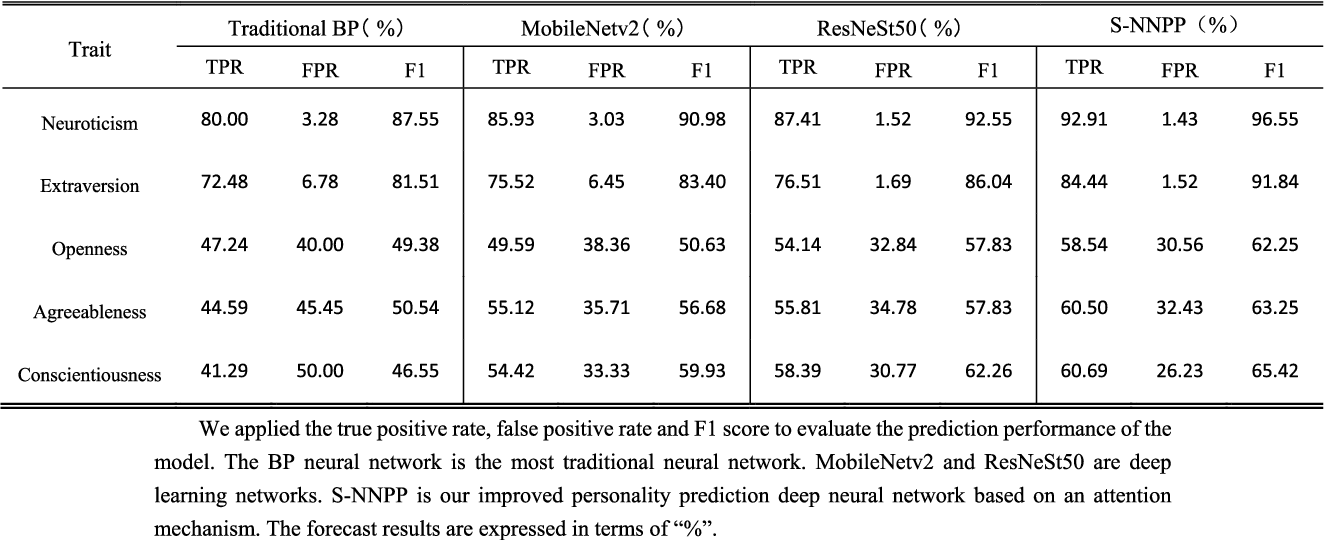

- It can even predict Big5 personality scores with impressive accuracy! 4

So, even before you exchange the first sentence with another person, you could make reasonable guesses about their interests, beliefs, opinions, and even their sexual orientation. This could be crucial (and private!) information, even if you’re not a British detective on a case. The “first impression” of another person can reveal a lot, and the brain likely uses such guesses to form a ‘feeling’ about a person. This could explain phenomena like “love at first sight” or why some people instantly like or dislike each other.

But we’ve only considered information visible in the first few seconds. Once you’ve sized up the other person, the conversation begins.

Speech

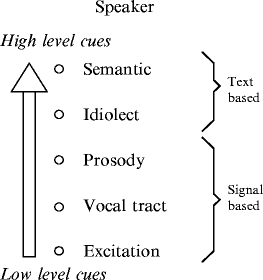

Human speech operates on several levels. We can infer information about a speaker from various levels, listed here from “low level” to “abstract”:

- Their prosody (i.e., the pattern of their intonations)

- Their language or (regional) accent

- The meaning of the spoken sentence

- The social context in which they utter a given sentence

Prosody

Starting from the bottom, the way a person talks can provide broad and surprising information. People were able to estimate both height and age with similar accuracy from voice as from a photo. Weight could also be estimated well, but with some gender differences: Male weight could be better estimated from a picture, while female weight could be better estimated from voice(!). Note that the study has a relatively low sample size. 5

Prosody is also used to infer mood, emotion, and engagement. But it can also predict personality traits. 6

Regional Accent

A regional accent is perhaps obvious: Using the accent, you can predict where a person (or their parents) grew up. This can then be used to infer a variety of statistical information, as factors like religious and political beliefs and education can vary substantially by region.

The meaning of spoken language

Given a spoken sentence, we get the information contained within it. For example, “I have a cute cat” implies that the speaker is a cat owner. At first glance, this is all the information contained in the sentence, but many pieces of information correlate. These are often called ‘prejudices’ and ‘biases’ as they prevent people from engaging with the individual and instead project their beliefs onto them. But statistically, these biases can be true. For example, during the corona crisis in the USA, vaccination doubt was strongly correlated to political belief. Most humans, however, do not possess exact statistical knowledge about such correlations, but use limited experiences from their life. Using Bayesian reasoning, we could accumulate several pieces of information a person is providing and then infer with high accuracy undisclosed knowledge. So a person that said A,B,C and D has a very high (>95%) chance of also believing E.

Social Context

This is a very high-level information channel, for which I have not yet found any literature. (Also because it seems really hard to experiment with!) Information here is bound mostly to the interpersonal level or to the convictions of the speaker. For example, sharing an intimate story not only contains the factual information about the story, but also implies that the speaker has a level of trust towards the listener.

Similarly, if the speaker does not want to talk about some belief, it implies a lower level of trust. A more complex example: speaking about controversial opinions provides information about the speaker’s willingness to be confrontational, or about his belief about the beliefs of the listener - he might not want to speak about these topics if he didn’t believe his opinion would be accepted by the other person.

There are even more information channels that are possible, such as various types of Body Language, Behavior, Attention, and even smell.

So why is this important? No human, except for the fictional Sherlock Holmes, is able to process this amount of information. But as we have seen, not only humans can process information of this type, but Deep Neural Networks can achieve higher accuracies than humans in many prediction tasks.

In other words, this technology exists and can be combined with Deep Learning:

We are inevitably heading towards a world where predictions about other people are supercharged using AI models. Not only in an economic setting or as a tool used by governments, but also in interpersonal communication. If this sounds like science fiction to you, you should note that ideas to use tools like this are not particularly recent.

The above image comes from a paper suggesting the use of AR tools to help autistic children improve their social communication. Note that similar to other tools that can help improve a human skill - for example, calculators - this could also be used to replace the human skill if technology progresses. Which it has. The image above is from 2018.7

If augmented reality technology becomes commonplace, tools like the ones described above will probably become commonplace too, radically transforming social interactions. This can be good or bad, but either way, the future will be weird.

Sources:

-

https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/publications/deep-neural-networks-are-more-accurate-humans-detecting-sexual ↩

-

https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.10739 ↩

-

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-79310-1 ↩

-

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9420736 ↩

-

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022103102005103 ↩

-

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-42504-3_16 ↩

-

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2018.00057/full ↩